Commission for Global Dimensions of Student Development

Friday, 21 June 2019 - 12:13pm

By Carli Fink

I often joke that the difference between student affairs in Canada and the United States can be summarized by mere punctuation: student affairs in Canada reminds me of a question mark, while student affairs in the U.S. feels like an exclamation point. That is, student affairs is not quite as defined, organized, or pronounced North of the 49th parallel as it is South. Talented, committed professionals do the work and do it well, but it happens… differently.

Picture: The Toronto, Canada skyline. The dome-shaped building is where the Toronto Blue Jays play their home games; the tower in the middle is the CN Tower.

I was raised in Canada, and attended a Canadian University for my undergraduate education. Despite being highly involved on campus, I never considered student affairs as a career path until a few years post-graduation. I recently completed an American graduate program in higher education and student affairs. I learned a significant amount through my coursework and practical experiences, but also by simply observing and comparing the higher education systems at play in each country. Here are a few of the major differences I noticed:

- Funding:

This, in my view, is the most significant difference, and the one that informs almost everything else. My American peers and colleagues are often surprised to hear that nearly all post-secondary institutions in Canada are publicly-funded. This means that there are far fewer institutions of higher education in Canada than in the United States, and that most Canadian post-secondary schools are quite large. Although each Canadian institution has its own culture and quirks, many are relatively similar in terms of price, curricular offerings, and outcomes.

When I moved to Boston for graduate school, I did not realize the extent to which small, private post-secondary institutions reigned in Massachusetts. Many people I have met associate prestige with exclusivity: that is, a prestigious institutions must be relatively small, because prestige is signaled and maintained through selective admissions. One of my American friends was shocked to learn that McGill University — among Canada’s most well-known — accepts nearly 50% of its applicants, and boasts a student body of over 40,000. The privately-funded institutions that do exist in Canada are not considered more prestigious; rather, they are simply faith-based, for-profit, or satellite campuses. To my knowledge, the singular non-denominational, non-profit post-secondary institution in Canada is Quest University in British Columbia. I understand that this difference might be less pronounced had I moved to the Midwest or the South, as public higher education is more prominent than private in these regions.

This semester, when the news exposed that many elite (mostly private) American institutions had been rocked by an admissions scandal, I felt this discrepancy more acutely than ever. For those interested in learning more about admissions in Canada, I recommend this article. Although a bit brash at points, I think it is interesting and fairly accurate.

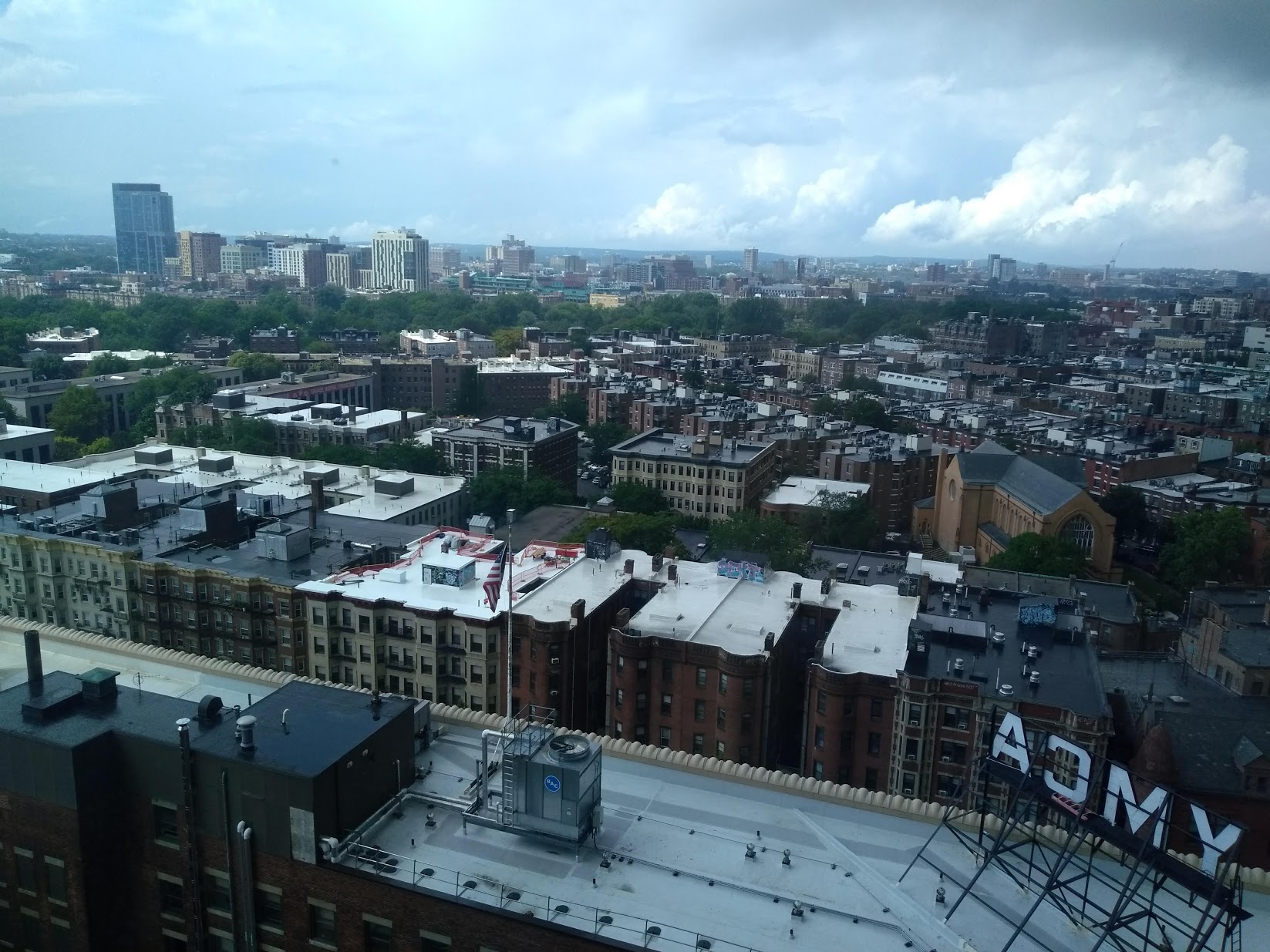

Picture: A view of Boston from the author’s residence hall room during summer 2018. The green bleachers in the center, behind the treeline, are Fenway Park.

2. Terminology:

What is a Community College, a College, or a University? Some of these terms may be described quite differently by a Canadian and an American, or even (especially in the case of Community Colleges) by two Canadians from different provinces. While the term “University” is generally used to denote a research institution in either country, many Americans use the terms “College” and “University” interchangeably to describe a degree-granting institution. “Colleges” often even exist within Universities, whereas these are known as “Faculties” in Canada. From a governance perspective, I should also note that there is no federal-level Department of Education in Canada; rather, each province’s Ministry of Education (or similar title) is the sole body responsible for all aspects of their provincial education systems.

With over 4,000 higher education institutions in the U.S., there is a lot more institutional diversity available to prospective students and employees. American institutions differ in significant ways: price, curriculum specialization, and educational philosophy are all far more variable. In Canada, this variety is equally likely to exist within institutions as between them.

Picture: At the author’s undergraduate institution, Orientation Week began with a parade where Orientation Leaders picked up first-year students from their residence halls and other places around campus. Carli, as an Orientation Leader, is behind the “Live Long and Froshper” sign.

3. Expectations and Services:

Student and family expectations of student services differ between the two countries, and influence how student affairs units deliver our services. I think that the extraordinarily high “sticker price” of attendance — particularly at private institutions — drives high expectations in the United States. Expectations are still high, but not as rooted in the logic of what a high price buys. I think Canadian practices and policies tend to view students as young adults, and emphasize their independence and self-advocacy. Relatedly, the prominence of rankings within American higher education can drive institutions’ goals and the services that are offered and prioritized. For example, academic advisors are commonly employed to maintain or increase rates of student retention and graduation, metrics that commonly factor into an institution’s rank on coveted lists. While rankings do exist in Canada, they hold far less influence.

Picture: Carli and two friends decked out in attire from their undergraduate institution. The hats, called “tams,” are a school tradition bestowed to students at the end of Orientation Week. The color of the pom-pom on top differs based on a student’s academic program. The tam is the basis of many historic traditions of the institution.

4. Functional Areas:

Hopefully, the above reasons begin to explain why certain “functional areas” of student affairs are more prominent in one country than the other. Residence life roles exist in Canada, but are less common — most students, particularly beyond the first year, commute from home or live in off-campus apartments. Greek life and athletics barely exist in Canada. Student activities, programming, and identity center jobs are also less available; many of these tasks may be rolled into one job, or these roles may be filled by (gasp) students.

In Canada, student governments (also known as student associations or student unions) are often separate legal entities from their host institutions. These entities often collect student fees that fund various programs and services on campus — almost like mini-student affairs divisions. My University’s student government provided full-time, salaried employment for over 30 students annually. These students oversaw the 300+ clubs on our campus, and operated over 10 services including an on-campus coffee shop, pub, peer counseling center, and unofficial campus book store. These services, in turn, provided part-time employment and leadership opportunities for hundreds more students per year. Considering how many of my peers performed substantial student affairs work during their undergraduate careers, it would be interesting to study how many pursued careers in the field!

With students filling these types of positions, student affairs departments tend to focus more on academic learning support, community engagement, peer mentorship, and health and wellness promotion (particularly given that the legal drinking age in Canada is 18 or 19, depending on the province). Roles in orientation, leadership development, international education, and career services are common in both countries. Perhaps it makes sense, given this diversity in positions, that student affairs professionals tend to come into the field from more diverse professionals backgrounds than is common South of the border. I don’t think either model is inherently better or worse, but have appreciated the opportunity to learn more about how each meets students’ needs.

I am often mistaken for an American student, but anyone who speaks to me about higher education and student affairs quickly learns otherwise. My classmates, colleagues, and professors know this well, and have participated in many comparative conversations with me over the past two years. It is thanks to them that my understanding of American higher education has developed so robustly.

Picture: Carli and two friends enjoying an evening at their undergraduate institution’s student-run campus pub.

Bio of Carli Fink

Carli has long been passionate about education outside of traditional classroom settings, and is grateful to the field of student affairs for providing her with a language to describe these interests and aspirations. Her professional experiences include high school guidance, Jewish campus life, academic advising, and health and wellness promotion. She holds a B.A. in Psychology, an M.S. in College Student Development and Counseling, and teacher certification. In her free time, Carli loves exploring new places and taste-testing the best ice cream in Boston.