Commission for Global Dimensions of Student Development

Sunday, 13 January 2019 - 11:54pm

I am from Austria. There, I said it. For the longest time, my identity as an international or foreign-born student/professional was not something I wanted to talk about. It wasn’t that I didn’t want to talk about my home country or background; I just got frustrated when people seemed to only be interested in this one aspect of my identity.

I first visited the U.S. on vacation with my family when I was 13 and then again when I was 15. When I was 16, I participated in a high school exchange program, and after I finished high school in Austria, I returned to the U.S. for college and never left (except for vacations and an unplanned one-year break during my doctoral program...but that’s a long story that is best saved for another day). From the very beginning – well, not during those family vacation but definitely as a high school exchange student – I didn’t want to be “that international student”; I just wanted to be one of “them” – the other students – and have a “normal” American high school and later college experience. Now, please don’t ask me what it means to have a “normal” American high school or college experience – I have no idea and I definitely didn’t back then, but it was what I wanted and I knew that being known as “the international student” was not part of that.

The high school I went to for my exchange year hosted three other exchange students that year. The other three – one from the Netherlands, one from Germany, and one from Italy – quickly became close friends. They bonded over being from another country and seemed to feel more comfortable spending time with each other than our American classmates. I, on the other hand, tried to avoid them. It wasn’t that I didn’t like them. But spending time with other Europeans didn’t fit into the picture I had of what my exchange year should be like. Instead, I joined as many after-school activities as possible and tried to be “just like the American students”. It worked and when I left, the closest friends I had made and those I visited and stayed in touch with, were my American classmates and not the other exchange students.

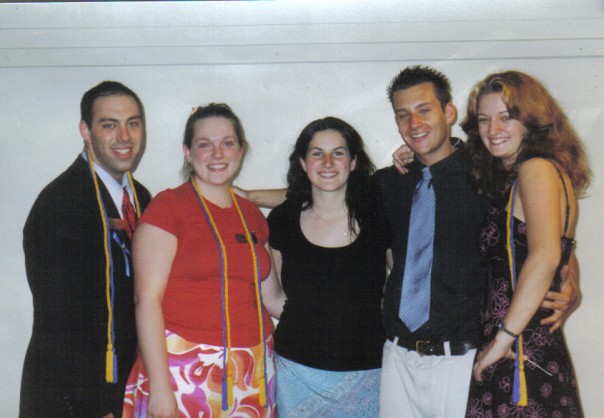

When I returned to college, I was again determined to have that “normal” American college experience. During international student orientation, I barely talked to the other international students; instead I quickly got to know my Orientation Leader, an American student. Once the semester started, I avoided all events geared toward international students. Instead, I got involved in various student organizations, became a Resident Assistant my second year, and made many American friends. I hated it, when people noticed my accent and asked me where I was from. It wasn’t that I didn’t want to share things about Austria or talk about Austria; I just always felt that, as soon as people knew, my foreign background became the only thing that seemed to matter to them. Instead of being Gudrun, the Resident Assistant and student leader (identities I had chosen and worked for), I was now Gudrun, the international student.

As I started working as a professional in Student Affairs, my struggles with my international identity didn’t go away. In some ways, things got worse because I now had to face job searching with the added burden of needing to find sponsorship. And that meant making my international background not just something that I talked about but something I had to sell as an asset and unique qualification. I remember being asked if I wanted to work with a living learning community for international students at a job interview. I didn’t know how to answer. I had avoided all international-themed events and organizations throughout college; I did not feel in the least prepared to work with international students, many of whom came from countries that were culturally more distant to me than U.S. culture. But I also really wanted to work at that institution and was worried how a “no” would be perceived. In the end, I admitted that working with international student was not really an interest area for; and fortunately, my answer was not a reason for the institution to not hire me.

But just a few years later, in another job search, I was told, after accepting a position as a hall director, that I would be placed in the building with the largest number of international students on campus and a global themed living learning community. The department believed that placing me in that community would provide them with a good argument in my visa sponsorship paperwork for why they wanted to hire me over other applicants. At that time in my life, I had started to accept my international identity more. I still would not have looked for an opportunity to work with an international population or a global themed community, but I was okay with it. And I knew that finding sponsorship and being approved for a non-immigrant work visas was getting harder and that I needed to do anything that could help with that process.

And so I became the expert for all things international in my ResLife department. And, to be honest, I actually really enjoyed working with that community and in many ways, this experience paved the way for me to embrace my international identity and let it become an important aspect of my professional life and career. Now, a few years later, I have written a dissertation on study abroad, am serving as Chair of the Commission for the Global Dimensions of Student Development, have built a network of international Student Affairs professionals, and am engaging in research on a variety of international-themed topics. But I still don’t like the question, “Where are you from?” Or worse, when I reply “Chicago”, and they – after picking up on my accent – ask, “No, where are you really from?” And yes, I have messed with people who asked that and played dumb, saying something like, “Oh, I lived in Maryland before that.” In general though, I no longer try to hide my international identity and instead value the unique perspectives it gives me with regard to the research I engage in and my work with students.

So why did I share this part of my story? I guess my hope is that this blog post will help readers recognize the danger of making assumptions about international students or colleagues. We often hear stories about international students seeking out friendships with other international students; we hear about a need to find better ways to connect international and domestic students. And yes, all that is true and initiatives to address these needs are needed. But, we also need to realize that “international student” or “foreign-born professionals” are broad terms that refer to a very diverse group of people. My experience different significantly from other international students because of other aspects of my identity such as being a White woman from a European country with highly educated parents. My reasons for coming to the U.S. differed greatly from many other international students; I wasn’t looking for career opportunities or advancement. I had had a great time in high school in the U.S. – school in the U.S. seemed a lot easier than in Austria and I enjoyed the opportunity to get involved in after-school activities and clubs – so I came to the U.S. because I thought college would be more “fun”. And I always traveling, so why not use my time spent in college getting to know another culture and another part of the world (which is also why I picked an undergraduate in another part of the U.S. than my high school had been; even if that not getting to attend college with any of my American high school friends).

A few years ago, I saw Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s powerful TedTalk about the danger of the single story. Her message – the importance of getting to know multiple stories and recognizing that one person’s story does not represent their entire country or race – resonated with me. My story does not represent what the experiences of all international students are like; it does not represent even the experiences of most Austrian international students. It is just my story and it should not be used to make assumptions about others who share one or more aspects of their identity with me.

But I also know I’m not the only international student who feels that way and I think professionals working with international students need to think about the needs of students like me as well. For example, while international students need some additional sessions on immigration paperwork during their orientation, are there ways to integrate their orientation with that of domestic students, so they get a chance to connect early on? And not connect in a program set up to bring together international and domestic students, but just connect as two first-year students starting college – without the focus being on the “international” part. In addition, what are institutions doing to help international students know about the resources and opportunities available on campus? Having gone to high school in the U.S. for one year, I had some advantages with regard to knowing how to navigate U.S. institutions and was able to find information on student organizations and involvement opportunities; but not everyone may. Maybe instead of international programs offices hosting many of their own programs, they could highlight and encourage students to attend events that are already happening on campus and are geared toward all students; I would have appreciated that information from the international programs office at my undergrad but instead only received information on trips only open to international students. If you are working in any functional areas, when an international student comes to you, don’t just send them to the international student office! Supporting international students and their needs is the job of all of us. And most importantly, if you are working with international students (which many of you are, no matter what functional area you are in), what are you doing to listen to their individual stories and learn about their unique needs? And, as a colleague of international Student Affairs professionals, what are you doing to learn about your colleagues and their stories – as international professionals but also as people with complex identities, experiences, and needs.

As chair of this commission, I have been excited to see some of that sharing of personal stories happen on our new blog, through Webinars, and at commission events at conventions. I am also excited to be part of a panel of international student affairs professionals at the 2019 ACPA Convention in Boston, sponsored by our commission. I hope many of our American colleagues will attend to learn more about the stories of international professionals in our field, the challenges we have all had to overcome to navigate a career in higher education in the U.S., and the unique ways we have been able to contribute to our campus communities and the field as a whole. I hope that these efforts will continue and that through future events and blog posts, we will move away from that “one story” about international students and professionals toward appreciating the diversity and beauty of the many stories of students and colleagues from around the world.

Bio of Dr. Gudrun Nyunt

Bio of Dr. Gudrun Nyunt

Gudrun currently serves as a Visiting Assistant Professor of Higher Education in the Department of Counseling, Adult and Higher Education at Northern Illinois University. Gudrun holds a PhD in Student Affairs from the University of Maryland, College Park; a Master’s in Higher Education and Student Affairs from the University of Connecticut; and a Bachelor’s in Journalism from the State University of New York at New Paltz. Prior to starting her PhD and transitioning to a faculty position, Gudrun worked for 7 years as a full-time staff member in Residence Life at Miami University, the University of North Florida, and the University of Connecticut. Gudrun also served as a Resident Director for the Fall 2012 Semester at Sea voyage.

Gudrun’s research interests revolve around educational practices that foster the development of intercultural maturity and prepare students for active engagement in a global society. In addition, Gudrun engages in research that strives to better understand the experiences of international, underrepresented minority, and women graduate students, faculty, and Student Affairs staff members at U.S. higher education institutions in hopes of promoting full participation of a diverse community in higher education.

Gudrun has been an active member of ACPA – College Student Educators for many years. She has been on the directorate boards of the Commission for Housing and Residential Life and the Commission for Student Involvement, and currently serves as chair of the Commission for the Global Dimensions of Student Development.